Suzanne Rankin-Dia, Academic Language and Communication Leader, Cert. HE. International Preparation for Fashion, London College of Fashion

This paper presents a curriculum initiative that aims to encourage the ‘internationalisation’ of international student experience. This initiative, entitled the ‘Global Citizenship Project’, is used on the Cert HE. International Preparation for Fashion (IPF) course at London College of Fashion. By describing the sources and approach used by tutors on the course, the paper explores the Global Citizenship Project brief given to students in the autumn term, and how it encourages student engagement with the immediate environment and one another. It explores how the curriculum should aim towards accepting and understanding the needs of multicultural learning, empowering learners to share their own cultural capital (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1994).

inclusivity, cultural capital, empowerment, engagement, internationalization, multiple perspectives

This paper starts from the premise that UK higher education institutions (HEIs) conform to a largely constructivist view of learning, whereby students construct their own knowledge through active participation. Given that current global student cohorts represent a range of learning backgrounds that may not conform to this constructivist view, there is a clear need for students to develop awareness through a learning process that is both empowering and inclusive. Many HEIs in the UK are currently working towards a model of increased student engagement, active participation and student-centred learning. The Framework for internationalising higher education, compiled by the Higher Education Academy (HEA), reiterates the importance of this process in relation to internationalisation, and how ‘promoting a high quality, equitable and global learning experience can help prepare graduates to live in and contribute responsibly to a globally interconnected society’ (HEA, 2016).

This paper will explore student engagement by presenting the ‘Global Citizenship Project’, an autumn term brief given to students on the Cert. HE. International Preparation for Fashion course (IPF) at London College of Fashion. The project aims to move away from the deficit model associated with international students (Ballard and Clanchy, 1997), towards an inclusive model that values multiple perspectives and learning approaches. The project supports Fox’s (1997) view that communicating interculturally connects and empowers students to value and share different perspectives and approaches. Zepke and Leach (2010) highlight a number of action points to improve student engagement, one such area is that of self-belief. Students with fixed self-theories tend to lack motivation at the first sign of failure, whereas students with malleable self-theories appear to be more open to accepting multiple perspectives in their learning. The Global Citizenship Project promotes an opening of self-theories using the ‘Open Spaces for Dialogue and Enquiry’ (OSDE) methodology developed by Andreotti, Barker and Newell-Jones (2006), to guide students towards creating a synthesized learning outcome. The aim of the curriculum initiative project is to provide a safe open space within a globally interconnected classroom, where students can explore their own identities in relation to others and learn to value their own cultural capital (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1984).

This paper combines action research with qualitative research in order to measure the impact of the Global Citizenship Project and OSDE approach on student learning. The insights it discusses have been acquired through staff and student reflection. Once confirmation from the LCF Research Ethics Committee had been obtained, I was able to proceed and gather perspectives from staff and students, evaluating the project.

International Preparation for Fashion (IPF) is a level 4 course aimed at preparing International Students for undergraduate study. It was established to address the gap in attainment between home and international students at UAL, as identified by Sovic (2008) and further examined by Sabri (2014). A unit on ‘Academic Language and Communication’ (ALAC) underpins the course and equips students with the academic capacities required for undergraduate study at LCF. The skills and competencies of HE academic study, along with language skills such as reading, listening, writing and speaking, are embedded into the unit and tested throughout, all of which use material that relates to the context of fashion studies. The unit is not streamed, but students who need to acquire more language are given extra, targeted support.

The spring and summer terms of the ALAC unit adhere to a different pedagogic approach, concentrating on Academic Literacies as a field of enquiry. Lilis and Scott (2007) argue that Academic Literacies based research at HE level prioritises academic writing over other forms of academic communication. This is due to a belief that ‘written texts continue to constitute the main form of assessment and as such writing is a “high stakes” activity in university education’ (Lilis and Scott, 2007, p.9). In the spring term, 40% of the assessment of the ALAC unit focuses on academic writing, and the academic literacies approach works well at this stage. By contrast, the autumn term is largely diagnostic in its focus, aimed at encouraging students to take ownership of their learning and develop their sense of self to find their way within a global society. The written assessment for the autumn term is a 500 word self-reflective statement considering each student’s learning process whilst undertaking the Global Citizenship Project. This uses OSDE methodology, asking them to respond to an initial question, ‘what are the challenges to a global citizenship education in an interdependent, diverse and unequal world?’. A principle aim is to encourage critical literacy and independent thinking by working within a wide-ranging conceptual framework that draws on multi-disciplinary approaches that encourage a critical engagement with knowledge (Andreotti, Barker and Newell-Jones, 2006).

The project encourages what Fanghanel and Cousin call ‘worldly pedagogy’ (2012). Worldly pedagogy allows space within the curriculum to harness diversity in order to bring about inclusivity, enabling students to share ideas and the values they bring with them, rather than encouraging them to adapt to the UK learning environment as quickly as possible. It involves:

eliciting and sharing narratives, cognitive disturbance, harnessing cultural dissonance through ongoing dialogue in a safe space which enables students to develop the ability to see plurality as richness. Exploring situatedness then substituting a posture of ‘critical distancing’ from origins and formative experiences. (Fanghanel and Cousin, 2012, p.49)

Creating an inclusive environment that encourages sharing in a global classroom is of vital importance and likely to provide international students with a perceived level of safety and reassurance.

Comparisons can be drawn between worldly pedagogy and ‘transformative learning’, which aims to develop autonomous thinking patterns. Transformative learning is the process of effecting change in a frame of reference (Mezirow, 1997; Cranton, 1994). A global classroom brings together a range of cultural and social capital, situated within a specific frame of reference, which contains values and concepts that shape the individual student’s view. Mezirow argues that once these frames of reference are set, ‘we have a tendency to reject ideas that fail to fit our preconceptions, labelling those ideas as unworthy of considerations’ (1997, p.5). Cranton (1994) evaluates the transition of transformative learning from theory into practice and outlines how establishing a fluidity when constructing frames of reference will develop students’ critical self-reflection. Before they can engage in critical self-reflection, students need to be empowered and understand the value of their cultural capital. The OSDE approach encourages openness and safety within the learning space, allowing students to create their own frame of reference within a group.

International students are likely to experience culture shock, language shock and academic shock at various points throughout the autumn term (Ryan and Hellmundt, 2005). Sovic, in writing specifically about the UAL context, refines these experiences to ‘integration with other students’, ‘English language’ and ‘academic socialisation’ respectively (2008). Despite these difficulties, as Ryan and Hellmundt argue (2005), international students arrive equipped with a valuable skillset. Working to this premise, the challenge faced by teachers on the course, was to design an autumn term project that would empower students to utilise their skillset and cultural capital. Staff wanted to introduce a level of participatory enquiry in the first project, without moving too far away from a model of learning students expected. As Reason describes, approaches to participatory enquiry involve ‘a living process of coming to know, rather than a formal academic method’ (1994, p.325). In order to encourage students to create fluid frames of reference, we used the principle aims of OSDE to create a framework that would directly respond to Sovic’s observations (2008).

A project brief was designed around a definition of global citizenship that focuses on inclusivity rather than separateness. It made use of another method, developed from Oxfam’s ‘think-learn-act’ approach:

The focus is rather on exploring what links us to other people, places and cultures, the (e)quality of those relationships, and how we can learn from, as well as about, those people, places, and cultures. (Oxfam, 2016)

By integrating Oxfam’s think-learn-act with ‘raised awareness’, described in Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning (1956), we created a brief aimed at encouraging critical, reflective and proactive learners within an HE fashion studies context.

The student project brief re-mapped the think-learn-act approach to create the following learning strategies:

(IPF/ALAC student brief, 2014)

- Think (be critical): considering critically what can be done about the issue and relating this to how it will be understood and trying to understand the relevance.

- Learn (be reflective): exploring the issue considering it from different viewpoints and trying to understand the whys, hows and what ifs.

- Act (be proactive): thinking about and taking action on the issue as an active global citizen, both individually and collectively.

The cohort was separated into 3 groups, who were each given the brief. Rather than address a global issue, students were encouraged to engage with local community art and design spaces and draw upon their own cultural capital to consider ‘glocal’ (a synthesis of local and global) issues within this context. They then created an outcome, which was the focus of a presentation, during which the group explained their application of the think-learn-act process and how it was applied in their project. Students demonstrated a high level of engagement and collaboration and came up with a wide range of creative responses including: a stop motion video of the number 55 bus as a multicultural micro-society; an analysis of representations of race through the sale of Barbie Dolls; and an illustrated map of Hackney drawn on a toilet roll.

The first project group responded to the number 55 bus route that connects three LCF sites: Mare Street, High Holborn and John Prince’s Street. Students within this group created a stop motion video that included their own sketches, representing their reflections on bus travel in London and how it serves as a leveler: a space where a cross-section of demographics co-exist for a shared purpose.

Through this group project on global citizenship, I have gained a deeper understanding of cultural capital. Meanwhile, I realised how important it is to be hyper-observant in life because we always can be amazed by the details of small little things. As the first ever group project, this was the very challenge for me to learn how to communicate and work efficiently with a team. (IPF student, 2014)

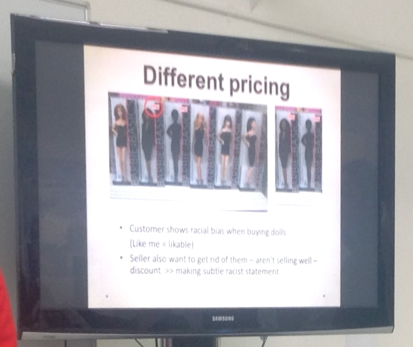

Whilst visiting an independent store in Elephant and Castle shopping centre, the second group were drawn to the range of ethnicities of Barbie Dolls displayed on the shop’s shelves. On closer inspection, they noticed some were on sale, but that only dolls with a black ethnicity were reduced in price. This became the focus of a process involving primary and secondary research, exploring representations of race and identity in children’s products.

I realised that the world is a big system where everything is linked together, but not always in the way we expect. I began to notice the global influence and cultural representations in our daily life. Every second of my life I use everyday objects which I never paid attention to before now. It was very useful for me to start thinking of simple things more deeply or in a different context ‐ it will help me to be more creative. (IPF student, 2014)

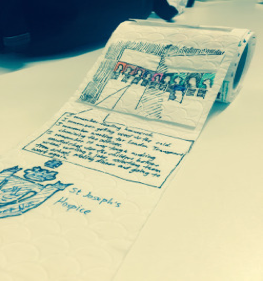

The third group responded to their initial, rather negative first impressions of Hackney. Students discovered a number of layers within the communities of Hackney and represented this through a series of original sketches, drawn on a toilet roll.

The toilet paper was an unexpected concept to explore, but I'm quite satisfied with the final object and the narrative we created around the toilet paper. The use of toilet paper, our video, and the drawings were all results of us having to work around the project parameters, which were to combining visual literacy, reflection, and global citizenship. (IPF student, 2014)

The project brief was designed to increase International Students’ confidence when speaking the English language. There is much speculation in HE around the relationship between language proficiency and attainment, however Sabri (2014) claims that, based on Mountford-Zimdars’ (2007-2008) statistical analysis, language proficiency is an unreliable indicator of attainment. My own experience of working with international students at UAL is more aligned with Sovic (2008), who argues that UAL students need English for communication rather than academic pursuit, particularly when they first arrive in the UK. Many anecdotal accounts show that having subject specific language was often less of a concern as many students have already studied the discipline in their home country. It is, instead, intercultural communication with peers that is challenging. Subsequently, the Global Citizenship Project was designed to be multi-functional and multi-dimensional. Each week had an input session: ‘Understanding the global’, ‘The global is local’, ‘Visualising the global’, ‘Verbalising the global’ and ‘Producing the global’ (Clarke, 2007). The input session took the form of a skills based classroom activity (listening, speaking, reading, writing) that was combined with academic vocabulary-building tasks and a self-directed primary research trip.

Throughout this autumn term unit, all students were directed to take ownership of their project by creating a group identity or brand; allocating roles within the group; setting rules and guidelines for their group and creating a group contract. Within this project management framework, students were empowered to understand their own skillset, learn from that of others and develop their academic language skills. Using these skillsets, students were able to negotiate roles within the group and find a common form of communication. In addition, by using social media and communication tools such as WhatsApp, students adapted to a shared intercultural communication. As Erard (2012) argues, native speakers also need to adapt their approach to using academic English as a ‘lingua franca’ ‐ a common language ‐ in order to understand diversity within variations of English, accents, cultural nuances and linguistic codes, as ‘academic language […] is no-one’s mother tongue’ (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1994, p.8).

Students worked in a mixed culture with mixed groups of nationalities and language levels. They managed their own project by documenting its development in continuous learning journals. The validity and legitimacy of their knowledge was encouraged as they constructed their own frames of reference, demonstrated by their varied creative responses to the brief. Due to this emphasis on self-direction, the role of the tutor became one of facilitation. Examples of the final self-directed outcomes include: a performance piece in the style of Korean and Japanese soap operas; a cross-cultural comparative analysis of graffiti art as displayed in London, Tehran and Shanghai; a multi-lingual animation; and a sub-titled documentary looking at Chinese, Korean and Japanese supermarkets in London.

The students on IPF acquired a range of academic skills throughout the process. They reflected on how they had developed these skills within the project and how to continue to build on these skills in a final exercise, in which students awarded themselves scores out of 10, comparing the level of skills they had when allocating group roles at the beginning with those they had developed by the end of the project. As a group we compiled a ‘Wheel of Reflection’, pictured in Figure 4.

This exercise revealed that more experienced students gained thinking and learning strategies, project management skills and an awareness of application and synthesis within a range of different disciplines. Feedback from this activity revealed that many students indicated that they had started to develop a relationship with their local environment and London as a resource for research.

The Global Citizenship Project was evaluated using the students’ continuous journal and group presentation, which were both formatively assessed, and the reflective statement produced by each student, which was summatively assessed. Throughout the project, students gave feedback on their engagement through the use of an ‘online padlet’ wall, as well as through the regular physical exercise of writing their thoughts on a post-it to create a wall of comparative notes. These shared resources were documented and then used by students to inform their reflective summaries.

Each group’s presentation delivery showed a high level of teamwork and confidence. On the whole, the reflective summaries demonstrated a clear awareness of the need for reflective practice with a creative context. In addition, students seem to have developed an understanding of the self as a global citizen, as one tutor on the project comments;

The Global Citizenship Project provides a holistic understanding by focusing students on their own self (cultural capital) in relation to a global community with particular focus on their sense of self in London. This project also opens up students to critical thinking by considering human values and beliefs, global systems, issues, history, cross-cultural understandings, and the development of analytical and evaluative skills. (IPF ALAC lecturer, 2015)

They also revealed awareness of the complexities of intercultural communication, which they are highly likely to encounter within the global fashion industry. Another project tutor suggests:

[The Global Citizenship Project] raises awareness of how communication is about negotiating meaning and accommodating speech to each other. It also highlights how intercultural communication is promoting tolerance of linguistic diversity. (IPF ALAC lecturer, 2015)

The Global Citizenship Project achieved short-term success in its aim to encourage student engagement with the immediate environment and one another, thus developing and empowering their collaborative communication skills. Student attainment in this respect is clearly indicated by the results/feedback detailed throughout this paper and importantly, it is supported by student comments:

…to do mostly primary research was a refreshing first for me. Also, our reflections and interpretations of the primary research as well as secondary research being the most main part of our project was something I've never been able to do in an academic setting. (IPF student, 2014)

This approach to learning, implemented at the very start of the academic year, seems also to have led to much more sustained engagement in the spring term, when students provided confident responses to their critical essay assignment on global consumerism, which achieved a pass rate of 84%. The project not only enabled students to undertake primary research, it boosted their confidence. As indicated by this student response, they gained a:

…comprehension regarding academic study, in an unexpected way and it is really helpful for the further study in this unit. This project has been a wonderful experience and helped me build up my confidence for my critical essay. (IPF student 2014/15)

In a wider academic context, working from Ryan and Hellmundt’s (2005) premise combined with the OSDE approach, this project has enabled tutors and academic staff to promote inclusivity within the learning space, enabling student voices to be heard equally without reliance on dominant cultures. This methodology and approach reduces the deficit view of international students (Ballard and Clanchy, 1997) and empowers both students and lecturers to challenge their perceptions and engage more confidently with intercultural discourses through critical reasoning.

In future, the Global Citizenship Project will be developed towards a ‘flipped learning’ approach that allows students to follow-up on their learning, creating more space for direct student-tutor discussion and collaboration. The project will continue to enhance focus on academic skills development through reflection by exploring the use of different platforms for displaying their project-role contracts and wheels of reflection, as these reflective tools raise awareness of individual development and further empower student self-awareness with regard to their learning. We aim to make stronger links with ‘glocal’ art and design communities and further enhance students’ sense of belonging in their local environment. In addition, we also aim to create an online exhibition forum, communicating Global Citizen Project outcomes to a wider audience, allowing students to share their achievements with friends and family all over the world.

Ballard, B. and Clanchy, J. (1997) Teaching students from overseas: a brief guide for lecturers and supervisors. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Andreotti, V., Barker, L. and Newell-Jones, K. (eds.) (2006). Open spaces for dialogue and enquiry methodology: critical literacy in global citizenship education, professional development resource pack. Derby: Centre for the Study of Social and Global Justice and Global Education Derby.

Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W. and Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. Handbook I: cognitive domain. New York; Toronto: Longmans, Green and Co.

Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J. (1994) ‘Introduction: language and relationship to language in the teaching situation’ in Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J., Martin, M. et al, Academic discourse: linguistic misunderstanding and professorial power. Translated by R. Teese. Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: a social critique of judgment of taste. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Clarke, M. (2007) Verbalising the visual: translating art and design into words. Lausanne, Switz.: AVA Academia.

Cranton, P. (1994) Understanding and promoting transformative learning: a guide for educators of adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Erard, M. (2012) Babel no more: the search for the world's most extraordinary language learners. New York: Free Press.

Fanghanel, J. and Cousin, G. (2012) ‘ ‘Worldly’ pedagogy: a way of conceptualising teaching towards global citizenship’, Teaching in Higher Education, 17(1), pp. 39-50, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.590973.

Fox, C. (1997) “The Authenticity of intercultural communication”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21(1), pp. 85-103 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223225966_The_Authenticity_of_intercultural_communication

Higher Education Academy (2016) Framework for internationalising higher education. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/enhancement/frameworks/framework-internationalising-higher-education (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Lillis, T. and Scott, M. (2007) ‘Defining academic literacies research: issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy’, Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1) pp. 5-32, http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1558/japl.v4i1.5.

Mezirow, J. (1997) ‘Transformative learning: theory to practice’, New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, Issue 74, pp. 5-12, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401.

Oxfam (2016) Oxfam education: global citizenship. Available at: http://www.oxfam.org.uk/education/global-citizenship (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Ryan, J. and Hellmundt, S. (2005) ‘Maximising international students’ ‘cultural capital’ ’, in Carroll, J. and Ryan, J. (eds.) Teaching international students: improving learning for all. London; New York: Routledge.

Reason, P. (1994) ‘Three approaches to participative enquiry’ in Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. (eds.) Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage. pp. 324-339.

Sabri, D. (2014) Becoming students at UAL: signing up to the intellectual project that is the course. London: University of the Arts London.

Sovic, S. (2008) Lost in transition? The international students’ experience project. London: Creative Learning in Practice, Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

Zepke, N. and Leach, L. (2010) ‘Improving student engagement: ten proposals for action’, Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(3), pp. 167-177, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469787410379680.

Zhou, Y., Jindal-Snape, D., Topping, K. and Todman, J. (2008) ‘Theoretical models of culture shock and adaptation in international students in higher education’, Studies in Higher Education, 33(1), pp. 63-75, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070701794833.

Suzanne Rankin-Dia has been working with International students at UAL since 2001, where she leads the pathway on ‘Academic Language and Communication’ on the Cert. HE. International Preparation for Fashion course at LCF. She is interested in how innovative and creative approaches can be implemented into classroom teaching, exploring how international students can reach their full potential, by encouraging the use of cultural capital and allowing them to make up their own rules.